Actors

- The protection and management of heritage places requires the collective work of a variety of actors, who can be individuals, institutions and/or other groups;

- Actors for heritage can be grouped in three broad categories: those who hold responsibilities (managers), those with rights over heritage (rights-holders), and those with interests in a heritage place but without rights over it (stakeholders).

- In some cases, the categories may overlap: rights-holders can also be managers if socially and legally empowered to be responsible and accountable for the conservation of the heritage place.

- The roles and responsibilities of managers for the heritage place are established through legal and/ or customary instruments and need to be analysed to help understand if the management system of the heritage place is effective.

- Collaboration and coordination between actors are the key to effective and equitable governance.

- Indigenous and community-based heritage management is increasingly recognized as effective for the conservation of heritage places and can bring many advantages.

- International human rights agreements must be respected for World Heritage All inherited assets which people value for reasons beyond mere utility. Heritage is a broad concept and includes shared legacies from the natural environment, the creations of humans and the creations and interactions between humans and nature. It encompasses built, terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments, landscapes and seascapes, biodiversity, geodiversity, collections, cultural practices, knowledge, living experiences, etc. conservation and management.

Protecting and managing heritage places involves a diversity of actors, including public institutions at various levels, elected officials, Indigenous Peoples, local communities, women and youth, private owners, businesses, non-profit organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), professional, religious or educational groups, and sometimes even intergovernmental international agencies. In the context of World Heritage All inherited assets which people value for reasons beyond mere utility. Heritage is a broad concept and includes shared legacies from the natural environment, the creations of humans and the creations and interactions between humans and nature. It encompasses built, terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments, landscapes and seascapes, biodiversity, geodiversity, collections, cultural practices, knowledge, living experiences, etc. , the term ‘actors’ refer to individuals, institutions or groups that hold rights, responsibilities and interests in the property and/or are involved in the conservation and management of the property. Such actors may hold such rights, influence, authority or responsibilities over the property through laws, plans, norms, traditions and other similar instruments, which determine their roles and the powers at their disposal.

Actors can be grouped in three broad categories: managers, rights-holders, and stakeholders. Often the term ‘stakeholder’ is used to refer to all these categories, however, the term ‘actors’ allows a distinction to be made between those who hold responsibilities (managers), rights over heritage resources (rightsholders),

and those with interests in a heritage place but without rights over it (stakeholders).

Managers are institutions and other types of entities, as well as the individuals working within them, which are recognized, responsible and accountable for protecting and managing the heritage place. Institutions responsible for managing the heritage place can be government-run, privately-owned and community-based. Indigenous Peoples, local and other community groups may also be managers by this definition operating through customary and traditional frameworks, if they are recognized by the broader society as accountable for the management of the heritage place. Managers can work at all levels including site level, local, regional, or national level, depending on the institutional framework and the country where the heritage place is located. Managers hold specific responsibilities towards the heritage place which is established through legal and/or customary instruments that provide such authority and accountability. The powers vested in managers can vary considerably depending on the type of heritage place, the nature of the governance arrangements and the distribution and balance of legal and customary authority they exercise.

Rights-holders Actors socially endowed with legal or customary rights with respect to heritage resources. In cases where there are Indigenous people involved, they have the right to free, prior and informed consent before approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, and need to participate in impact assessment. hold formal legal and/or customary rights over the heritage place or resources within it. Rights-holders Actors socially endowed with legal or customary rights with respect to heritage resources. In cases where there are Indigenous people involved, they have the right to free, prior and informed consent before approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, and need to participate in impact assessment. can be Indigenous Peoples with a long-lasting relationship to the heritage place, private owners, people residing in or around the heritage place, a religious group or entity responsible for upholding a sacred place, and groups with rights to use resources within the property or buffer zone, among others.

Stakeholders

In a World Heritage context, stakeholders are those who possess direct or indirect interests and concerns about heritage resources, but do not necessarily enjoy a legally or socially recognized entitlement to them.

In impact assessment, stakeholders are individuals or groups that may be affected by a project, or someone or an organization who represents such people. Collectively, the two are sometimes referred to as ‘interested and affected parties’.

possess direct or indirect interests, concerns and influence over the heritage place but do not enjoy a legally or socially recognized entitlement to the heritage resources.

Stakeholders

In a World Heritage context, stakeholders are those who possess direct or indirect interests and concerns about heritage resources, but do not necessarily enjoy a legally or socially recognized entitlement to them.

In impact assessment, stakeholders are individuals or groups that may be affected by a project, or someone or an organization who represents such people. Collectively, the two are sometimes referred to as ‘interested and affected parties’.

in a heritage context can be, for example, interest groups, businesses, or tourism operators.

Managing a heritage place requires navigating between myriad interests and expectations from different actors with different powers to influence decision-making processes. Power can take many forms and operates both through formal and informal systems, through established institutions and rules, and personal relationships and cultural norms. In the context of heritage management, power is present in the interactions and relationships between actors and within groups and institutions.

Understanding these power relationships is important when analysing governance arrangements and decision-making processes related to the management of the heritage place, however, there may be hidden or implicit elements which can be difficult to identify. For instance, in some situations, certain rights-holders groups because of their economic resources may voice their interests more strongly than economically deprived ones. Or certain business companies whose interests align with political agendas may hold more lobbying powers than rights-holders or managers.

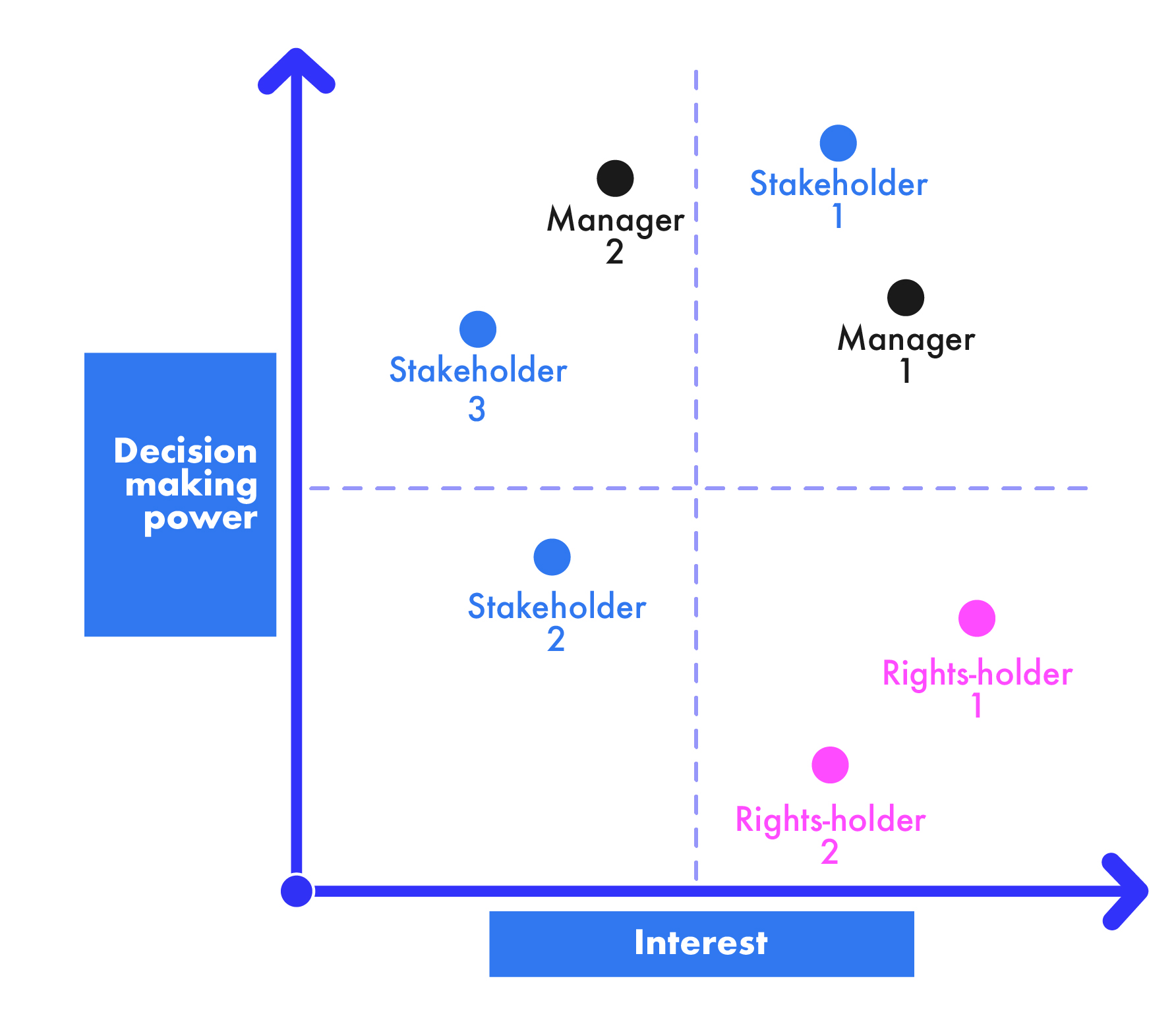

In order to consider these complex situations and identify power relationships it can be helpful to carry out an analysis. An example of how this might be done is given in Figure 4.1, where different actors have been positioned in a matrix according to their relative decision-making power about the management of the heritage place and interest in conserving the heritage place. This analysis can be used to prompt improvements in heritage management while respecting rights-holders’ legitimacy to benefit from using heritage resources.

Figure 4.1 This example of analysing the actors of a heritage place in terms of their relative power and interest can be a helpful first step in understanding their influence on decision-making. Consideration of the current state of play can lead to reflection on which actors need to be supported in their roles and responsibilities towards the heritage place – and where caution might be needed.

Some examples of how such analysis can be applied are given here, on the basis of the hypothetical analysis in Figure 4.1:

- Rights-holders Actors socially endowed with legal or customary rights with respect to heritage resources. In cases where there are Indigenous people involved, they have the right to free, prior and informed consent before approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, and need to participate in impact assessment. 1 and 2 have less decision-making power than stakeholders 2 and 3, despite having rights over heritage resources and having more interest in conserving the place, questioning whether governance arrangements should be adjusted to recognize their rights and involve them more in decision-making;

- Manager 2 holds a lot of power but is not very interested in conserving the heritage place, maybe because her mandate is not heritage specific and she doesn’t fully understand the significance of the heritage place; efforts are needed to involve this manager more, and to explain why the place is important;

- Stakeholder 1 has no rights or heritage responsibilities over the management of the place and little interest in conserving it but has a disproportionate amount of power; governance arrangements need to be revised to ensure that decision-making processes are transparent and inclusive in order to balance the interests of different actors and to avoid decisions that could have negative impacts on the heritage place and rights of associated communities.

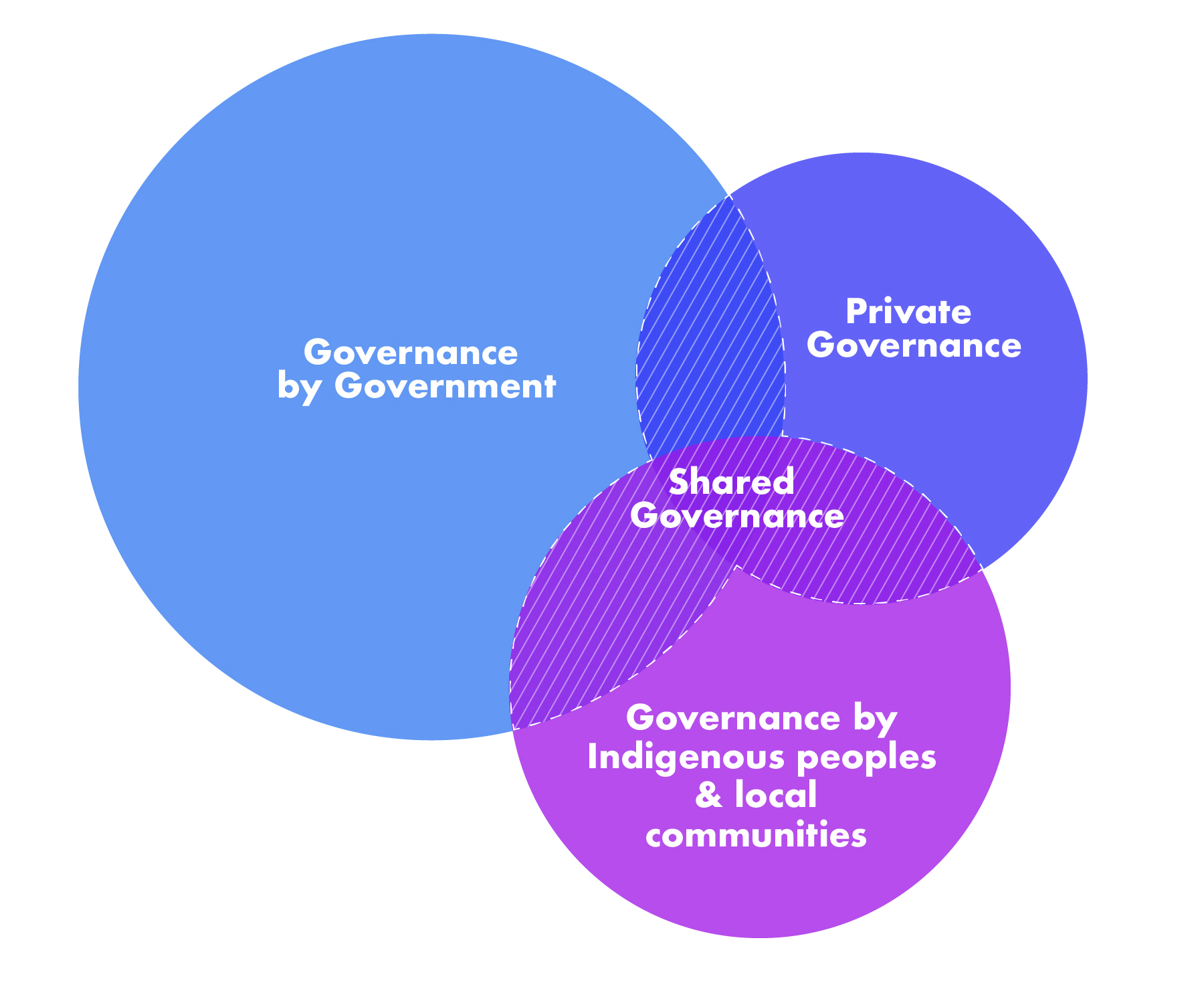

Governance arrangements can vary considerably from one heritage place to another. Some heritage places are mainly managed by one or more government institution whereas others are under shared governance by different actors, including a mix of governmental, non-governmental and private actors. For World Heritage All inherited assets which people value for reasons beyond mere utility. Heritage is a broad concept and includes shared legacies from the natural environment, the creations of humans and the creations and interactions between humans and nature. It encompasses built, terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments, landscapes and seascapes, biodiversity, geodiversity, collections, cultural practices, knowledge, living experiences, etc. properties, there is always some governmental oversight – even when on a regular basis they are managed by private entities, religious associations or groups acting on behalf of Indigenous Peoples or associated communities – since the ultimate responsibility for protecting the property lies with the State Party. Some governance arrangements could apply to the entire heritage place or there could be a mixture of arrangements for different parts of the heritage place. In such cases, understanding who is truly responsible for managing the heritage place is critical.

Managers’ responsibilities towards the heritage place are established through legal and/or customary instruments. These instruments also grant them powers and the degree of influence they can exert when managing the heritage place. Such powers can include:

- planning powers which refer to the capacity to establish management objectives and develop management plans and other planning instruments;

- enforcement powers which refers to the capacity to enforce decisions, rules and regulations through a variety of means, including social pressure, means of surveillance, and the imposition of fines and other sanctions. In cases where managers do not directly hold this power, it is necessary to establish partnerships with legal institutions that can exercise this power (e.g. police);

- spending powers which refer to the capacity to use the resources allocated to plan management actions and implement them as well as to enforce rules, develop and maintain infrastructure, and undertake capacity-building and research;

- revenue-generating powers which refer to the reception of fees, licensing and permits to access and use the heritage place;

- coordination power which refers to convening other relevant actors and developing agreements with them as well as delegating them some of the above mentioned powers. This power is connected to knowledge and know-how and refers to the possession of relevant information and skills that enable managers to define what type of knowledge is needed, how it can be acquired and used to support specific decisions, and the communication of information related to decision-making or the use of dissemination platforms.

Unlike other actors, managers are expected to be in charge of a heritage place in full capacity. Most importantly, they are considered accountable for the management of the heritage place. This fundamental distinction is critical to distinguish between managers and rights-holders.

Many heritage places are managed by institutions or groups acting on behalf of Indigenous Peoples and/or local communities through customary, legal, formal or informal mechanisms and rules. Community-based management is increasingly recognized as effective for the conservation of heritage places, especially when it follows more holistic approaches to the interconnections between cultural and natural heritage compared with conventional government-led management systems, which tend to divide the two from an administrative or institutional perspective.

Figure 4.2 Different types of governance for heritage places. Source: Adapted from IUCN Protected Areas Governance Types (2013).

There can be many advantages to Indigenous and community-based heritage management. Indigenous Peoples and other communities associated with heritage have capacities that can outlast political or professional governance structures and cycles. Many places now designated as heritage have been protected over long periods of time with resources, knowledge and skills provided by successive generations. The participation of these actors in management makes it possible to have multiple voices, views and forms of knowledge that allow good decisions to be made that have relevance for the entire heritage place. The diverse local, traditional and Indigenous knowledge systems combined with science can provide a powerful base to form locally appropriate, culturally diverse and sensitive management policy and actions.

Regrettably, in many heritage places certain rights-holders groups have been historically dispossessed from accessing and using ancestral lands, community areas or other heritage by government, private companies and other actors. Such actions have been subject to a mixture of approaches from soliciting voluntary limitations of their rights to enforcing actions with a degree of coercion. It is now fully recognized that Indigenous Peoples must give their free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) before designating a place as heritage and should never be forced or coerced by violent means to do so. Fortunately, customary rights relating to heritage protection, land tenure, and use or resource exploitation, are increasingly being recognized, nationally and internationally, although stronger and sustained efforts to protect these rights are continuously needed.

In order to empower Indigenous Peoples and associated communities to take the lead over the management of their heritage places, government institutions officially responsible for the heritage place need to transfer or share responsibility for decision-making in a variety of ways. Such processes need to be formally recognized and accompanied by adequate technical and financial resources, to ensure that the groups or institutions acting as representatives of the Indigenous and associated

communities have the capacities to assume their roles and responsibilities as managers. There are many different forms of shared governance and co-management. In some cases, partnerships have been established between Indigenous Peoples and governmental institutions, so that the institutional resources can support the community’s decisions regarding heritage conservation. In other cases, legal title to the land within the boundaries of the heritage place has been transferred to Indigenous Peoples, sometimes with lease-back arrangements put in place.

With respect to community relocations to establish heritage places or for any other conservation purpose, international human rights agreements, and in particular the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), must be respected for World Heritage All inherited assets which people value for reasons beyond mere utility. Heritage is a broad concept and includes shared legacies from the natural environment, the creations of humans and the creations and interactions between humans and nature. It encompasses built, terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments, landscapes and seascapes, biodiversity, geodiversity, collections, cultural practices, knowledge, living experiences, etc. conservation and management. In accordance with these agreements, Indigenous Peoples shall not be removed from their lands or territories without their free, prior and informed consent.

- Is it clear who the managers are in your heritage place? If not, why not?

- In cases where there are several managers, is it clear which managers hold the primary responsibility for managing the

World Heritage property

A cultural, natural or mixed heritage place inscribed on the World Heritage List and therefore considered to be of OUV for humanity. The responsibility for nominating a property to the World Heritage List falls upon the State(s) Party(ies) where it is located. The World Heritage Committee decides whether a property should be inscribed on the World Heritage List, taking into account the technical recommendations of the Advisory Bodies following rigorous evaluation processes.

When used as a general term, World Heritage refers to all the natural, cultural and mixed properties inscribed on the World Heritage List. ? Are those primary managers also responsible for the management of the buffer zone? If not, what challenges derive from a separation in management responsibility between the property and buffer zone? - Is it clear what instruments and powers grant each manager the authority, role and responsibilities over the property and/or the buffer zone? How do those instruments and powers make them accountable to the other actors?

- Are there any conflicts or overlaps between the responsibilities of different managers?

- Have all rights-holders groups been identified? Are the rights of each group well understood?

- Are the rights of different groups respected by all managers? Are customary rights which support the conservation of the heritage place respected to the same extent as legal rights?

- Is the practice of some customary rights in conflict with the management objectives for the property?

- Are all rights-holders’ groups engaged in the management of the property? Do some feel excluded?

UNESCO, ICCROM, ICOMOS, IUCN (2023). Tool 4 Governance Arrangements in Enhancing Our

Heritage

All inherited assets which people value for reasons beyond mere utility. Heritage is a broad concept and includes shared legacies from the natural environment, the creations of humans and the creations and interactions between humans and nature. It encompasses built, terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments, landscapes and seascapes, biodiversity, geodiversity, collections, cultural practices, knowledge, living experiences, etc.

Toolkit 2.0, pp. 46-56, Paris, UNESCO.

Borrini-Feyerabend, G. Dudley, N. Jaeger, T. Lassen, B. Pathak Broome, B. Phillips, A. and Sandwith, T. (2013). Governance of Protected Areas: From understanding to action, Gland (Switzerland), IUCN

UNESCO, ICCROM, ICOMOS, IUCN (2012). Managing Cultural World

Heritage

All inherited assets which people value for reasons beyond mere utility. Heritage is a broad concept and includes shared legacies from the natural environment, the creations of humans and the creations and interactions between humans and nature. It encompasses built, terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments, landscapes and seascapes, biodiversity, geodiversity, collections, cultural practices, knowledge, living experiences, etc.

, UNESCO Paris, UNESCO.