Actors

- Who are the actors in a heritage place, their roles and responsibilities

- The difference between managers, rightsholders and stakeholders

- The relationship between power and interest of the different categories of actors

- The powers and responsibilities of managers

- What is needed for an equitable and effective governance

- How rightsholders can become managers

Protecting and managing heritage places involves a diversity of actors, which are not solely tied to the institutions of government. Actors may also include other institutions at various levels, elected and traditional authorities, Indigenous peoples and local communities, women and youth, private owners, businesses, non-profit trusts, NGOs and international agencies, professional organisations, religious and educational organisations, etc. Such actors hold rights, influence, authority and responsibilities over a heritage place through laws, plans, norms, traditions and other similar instruments, which determine their roles and powers at their disposal.

In the context of heritage management, the term actors refer to all the individuals, as well as the institutions and/or groups they represent, that are involved directly and/or indirectly in the conservation of a

World Heritage property

A cultural, natural or mixed heritage place inscribed on the World Heritage List and therefore considered to be of OUV for humanity. The responsibility for nominating a property to the World Heritage List falls upon the State(s) Party(ies) where it is located. The World Heritage Committee decides whether a property should be inscribed on the World Heritage List, taking into account the technical recommendations of the Advisory Bodies following rigorous evaluation processes.

When used as a general term, World Heritage refers to all the natural, cultural and mixed properties inscribed on the World Heritage List.

or heritage place. Three broad categories of actors are distinguished: managers, rightsholders and stakeholders.

Managers refer to institutions and other types of organisations, as well as the individuals working within these, which are recognised, responsible and accountable for protecting and managing the heritage place. Managers can work at site level, regional or national level, and other levels of government, including community level, depending on the political system used in the country where the heritage place is located.

Rightsholders are socially endowed with legal and/or customary rights over the heritage place but are not directly responsible for its management. Rightholders can be Indigenous peoples having a long-lasting relationship to the heritage place, local communities residing in or around the heritage place, associations with rights to the use of resources within the property or buffer zone, women and youth, among other groups.

Stakeholders

In a World Heritage context, stakeholders are those who possess direct or indirect interests and concerns about heritage resources, but do not necessarily enjoy a legally or socially recognized entitlement to them.

In impact assessment, stakeholders are individuals or groups that may be affected by a project, or someone or an organization who represents such people. Collectively, the two are sometimes referred to as ‘interested and affected parties’.

possess direct or indirect interests, concerns and influence over the heritage place but do not necessarily enjoy a legally or socially recognised entitlement. This term has been largely used in the context of heritage management to encompass all actors, however, the term actors allows the distinction between those that hold responsibilities (managers) and rights (rightsholders) over a heritage place beyond interest (stakeholders).

Stakeholders

In a World Heritage context, stakeholders are those who possess direct or indirect interests and concerns about heritage resources, but do not necessarily enjoy a legally or socially recognized entitlement to them.

In impact assessment, stakeholders are individuals or groups that may be affected by a project, or someone or an organization who represents such people. Collectively, the two are sometimes referred to as ‘interested and affected parties’.

in a heritage context can be business operators, tourism companies, NGOs working on the protection of the heritage place but also, those dedicated to other aspects of development of local communities in the heritage place which may influence conservation.

These categories are not restrictive and may sometimes overlap, when in some cases, for instance, rightsholders may also be recognised as managers of a heritage place even if they do not formally represent an organisation. The distinction lies in whether the rightsholder has responsibilities for managing the heritage place vis-à-vis other members of the community or society. As well, some rightsholders could be considered as well stakeholders, as they might develop interests beyond their rights in the heritage place. This could be the case when residents of a historic centre favour tourism development policies acting as stakeholders, against residents that denounce gentrification, acting as rightsholders.

The actors involved in decision-making over the heritage place (or who are not currently but should be) will vary depending on a variety of aspects including the typology of heritage assets and the social, economic and environmental context. Associated with each actor will be laws, plans, norms, traditions and other instruments that determine the rights, influence, authority and responsibilities it holds over a heritage place, its strategic priorities and relationships with other actors.

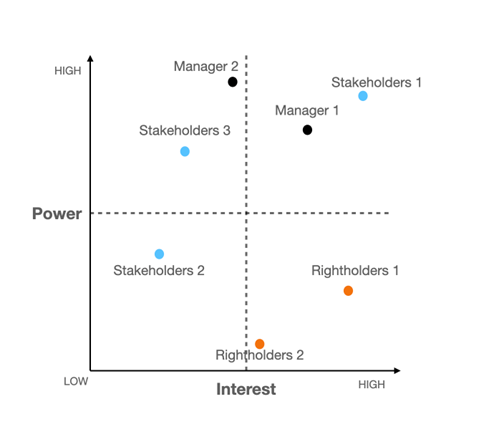

Power takes many forms, operates both through formal and informal systems, through established institutions and rules, and organic relationships and cultural norms. In the context of heritage management, power is present in the interactions and relationships between actors and within groups and institutions[1]. This power interplay is crucial when analysing governance arrangements and decision-making processes related to the management of the heritage place. In many heritage places, managers, which are representing the government authority, tend to hold more power for taking decisions about their conservation than rightsholders that inhabit the heritage place, and sometimes, stakeholders may hold more power than rightsholders - sometimes even more than managers - when their interests are in line with high level political agendas.

The following graphic adapted from a stakeholders matrix analysis can be useful to identify power relationships between actors in a heritage place (Figure x). There can be different groups for the different categories and each could have more or less power as well as more or less interest. Managers, who do not only hold power and interest but also responsibility over the heritage place, need to understand these power relations in order to catalyse efforts for the protection of the heritage place. Managers should be able to balance different interests in order to achieve the conservation of heritage values.

Figure X.

Stakeholders

In a World Heritage context, stakeholders are those who possess direct or indirect interests and concerns about heritage resources, but do not necessarily enjoy a legally or socially recognized entitlement to them.

In impact assessment, stakeholders are individuals or groups that may be affected by a project, or someone or an organization who represents such people. Collectively, the two are sometimes referred to as ‘interested and affected parties’.

analysis.

Managers’ responsibility towards the heritage place is established through legal and/or customary instruments. These powers include:

- planning and regulatory powers which refer to the capacity to develop meaningful conservation objectives and effective rules concerning access to the heritage place and which are usually included in a management plan;

- the power to enforce which refers to the capacity to enforce decisions and rules through a variety of means, including social pressure, means of surveillance, and the imposition of fines and other sanctions. In some cases, managers do not hold directly this power but can establish partnerships with legal institutions that can exercise this power (e.g., police);

- spending powers which refer to the capacity to use the resources allocated to enforce rules and implement surveillance, develop and maintain infrastructure, implement conservation projects, hiring staff and undertake training and research;

- revenue-generating powers which refer to the reception of fees, licensing and permits to access and use the heritage place;

- coordination power which refers to convening other relevant actors and developing agreements with them as well as delegating them some of the above-mentioned powers. This power is connected to the power of knowledge and know-how which refers to the possession of relevant information and skills that enable managers to define what type of knowledge is needed, how it can be acquired, and also use knowledge to support specific decisions and the communication of information related to decision making or use of dissemination platforms.

Unlike other actors, managers are expected to oversee a heritage place in full capacity, which grants them with the power of time to be dedicated to management and conservation tasks. One or several managers, depending on the heritage place, should possess some or all the powers above, although to a widely varying degree, which demands the collaboration and coordination between the different managers and other relevant actors.

Achieving effective and equitable governance and management requires coordination and collaboration among actors with rights and responsibilities over the heritage place. Much more can be achieved when people work together, particularly by building stronger partnerships across administrative levels. This allows to combine resources to attain goals that previously may have looked impossible or difficult and to explore collaborative solutions to management challenges. In order to achieve successful collaborations, legal and customary frameworks, actors, and decision-making processes need to be understood to assess and improve the existing governance arrangements.

Effective and equitable governance will vary according to the mandate, capacity and resources of the actors involved, if and how their role and responsibilities are recognised and respected as well as the availability of platforms and processes to facilitate exchange. Coordination will depend on certain conditions including:

- Involvement of all those having the capacities necessary to assume their roles and responsibilities;

- Showing mutual respect among those involved;

- An active dialogue sustained and consensus sought on solutions that meet, at least in part, the concerns and interests of everyone and are aligned with broader sustainable development and resilience agendas;

- A learning culture that favours new ideas and carefully allowing testing and promoting innovation;

- A shared journey to develop (or consolidate) and pursue an inspiring and consistent strategic agenda for the heritage place and define and achieve its conservation and management outcomes.

Indigenous and local communities have capacities and assets that outlast political or professional structures and complement specialist knowledge and skills. The engagement of these rightsholder groups in the management of heritage places brings advantages especially when heritage places are considered to be an instrumental part of community identity. The participation of these actors in management makes it possible to have multiple voices, multiple views and multiple forms of knowledge that would allow good decisions to be made in relevance to the entire heritage place.

In many heritage places though, rightsholders, including Indigenous peoples, local communities and certain social groups, have been historically dispossessed from their rights to access and use of ancestral lands or community areas by government, private companies and other stakeholders. However, customary rights that used to be respected and enforced traditionally, and that may have been overridden by modern legal systems of heritage protection or resource exploitation, are increasingly being recognised again at international and national levels. Still, customary rights and private ownership do not necessarily fully entitle rightsholders. Legislation in certain designated heritage places may limit ownership, and in some cases, it may have expropriated land and resources, such as in the case of many protected areas, or control uses that may include holding rituals as it is the case in some archaeological sites.

For enabling these rightsholders groups to take the lead over the management of their heritage places, power needs to be decentralised whereby government institutions officially responsible for the heritage place devolve responsibility for decision-making to these communities, through different organisations, or a governmental agency relegating authority to a local organisation. It is important to note that problems can arise when responsibility for decision-making is devolved without the necessary power or resources to act. Therefore, the process of granting the management responsibility to rightsholders needs to be accompanied by the creation of the necessary structure that would provide rightsholders with legal, financial and other resources as well as with capacities to adequately exercise their managing tasks.

For protected and conserved areas, IUCN defined four types of governance, with one referring to those managed by Indigenous peoples and/or local communities through customary, legal, formal or informal institutions and rules. An example are the Indigenous Peoples’ and Community Conserved Territories and Areas (ICCAs) which describe those ecosystems that are under the management of Indigenous peoples and local communities through customary laws and other effective means. This type of community-based governance is increasingly recognised as effective for biodiversity conservation[2]. In the case of cultural heritage, particularly for cultural landscapes, the management of the property might be shared between rightsholders and governmental institutions, and in some cases, fully the responsibility of one or various local communities and/or Indigenous groups. These groups will not only care for the natural resources, but also for their built heritage, intangible cultural heritage and traditional infrastructure, like water systems, terraces, canals, etc.

For these types of governance arrangements to be effective, Indigenous peoples and/or local communities must be organised to take decisions and develop rules for the management of land, water, natural and cultural resources. These customary and/or local institutions are complex, place and community-based and might differ from heritage place to heritage place. To function adequately, these communities need to be recognised as legal subjects by governments, and be granted officially the management of the heritage place. Yet, these conditions may be more difficult to achieve in certain countries than others, even when community-based management could be contributing already to conservation.

- The protection and management of heritage places require the collective work of a diversity of actors, which can be individuals and/or institutions which are not only attached to governments.

- Managers, rightsholders and stakeholders are the three main categories of actors in a heritage place. These categories may overlap: rightsholders can also be managers if socially and legally recognised to be responsible and accountable over the conservation of the heritage place.

- Governance in a heritage place reflects power and interest relationships between different actors. Their roles and responsibilities need to be analysed to understand and improve the governance and management system of the heritage place.

- Collaboration and coordination between actors and especially between managers, and between managers and other relevant actors, is key for an effective and equitable governance.

- Rightsholders, in particular Indigenous peoples and local communities, need to be empowered legally, financially and socially[2] in order to effectively assume the role as managers of a heritage place.

Reflection questions

- Is it clear which are the managers in your heritage place? If not, why not?

- Is it clear what instruments and powers grant each manager the authority, role and responsibilities over the property and/or the buffer zone(s)? How do those instruments and powers make them accountable to the other actors?

- In cases where there are several managers, is it clear who holds the primary responsibility for managing the

World Heritage property

A cultural, natural or mixed heritage place inscribed on the World Heritage List and therefore considered to be of OUV for humanity. The responsibility for nominating a property to the World Heritage List falls upon the State(s) Party(ies) where it is located. The World Heritage Committee decides whether a property should be inscribed on the World Heritage List, taking into account the technical recommendations of the Advisory Bodies following rigorous evaluation processes.

When used as a general term, World Heritage refers to all the natural, cultural and mixed properties inscribed on the World Heritage List. from a heritage perspective? Is that manager also responsible for the management of the buffer zone? If not, what challenges derive from a separation in management responsibility between the property and buffer zone? - Is the mandate for the property’s primary manager adequate for the required role? Does that mandate and the instruments at its disposal grant the manager the necessary powers to effectively assume the primary responsibility for managing the property?

- Are there any conflicts or overlaps between the responsibilities of different managers?

- Have all rights-holder groups been identified? Are the rights and responsibilities of each group well understood?

- Are the rights of different groups respected by all managers? Are customary rights respected to the same extent as legal rights?

- Is the practice of some customary rights in conflict with the management objectives for the property?

- Do rightsholders' practices positively contribute to the protection and management of the property?

- Are rightsholders' groups engaged in the management of the property? Do some feel excluded?

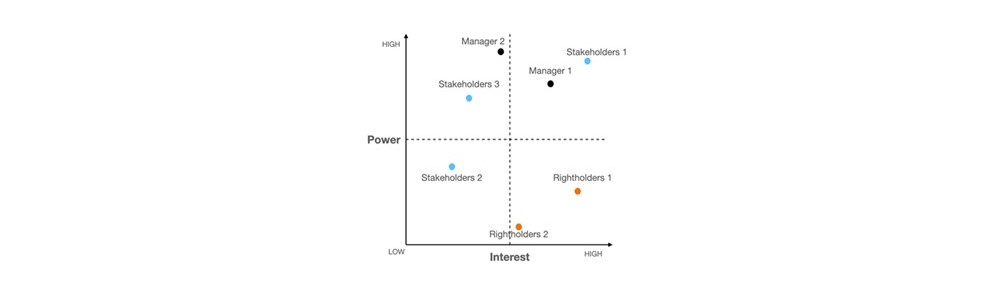

Figure X.

Stakeholders

In a World Heritage context, stakeholders are those who possess direct or indirect interests and concerns about heritage resources, but do not necessarily enjoy a legally or socially recognized entitlement to them.

In impact assessment, stakeholders are individuals or groups that may be affected by a project, or someone or an organization who represents such people. Collectively, the two are sometimes referred to as ‘interested and affected parties’.

analysis.