Management planning processes

Planning can be defined as the process used to establish how to get from the present situation (here) to a desired state in the future (there). This requires a clear understanding of the present situation before deciding what is to be achieved, what actions to take, what the timeframe will be, what resources are needed and who will be responsible for the implementation of the actions defined. People often reduce the planning process for a heritage place to the development of the management plan or similar instrument. But planning is not simply an event. Instead, it is best seen as a sequence of iterative stages and that is why it is defined as a process, emphasising its ongoing nature. How the management plan is developed is as important as the content of the plan itself. The plan must also be developed within a broader planning framework which will influence its scope. Likewise, governance arrangements will determine who is responsible for leading the planning process and who must be involved. Plans also affect rightsholders and stakeholders, which is why planning should be a participatory process from the beginning.

Management plans offer guidance for future management but achieving desired outcomes is difficult as unforeseen circumstances may disrupt the implementation process. Therefore, to a certain extent, management plans should be developed as flexible documents, able to evolve as conditions change. The period of time extending from the beginning of the development of the plan until it is due to be reviewed or replaced by a new one is defined as the management cycle. The duration of this cycle (e.g. 3, 5 or 10 years) will influence what desired outcomes can be achieved and consequently the nature of the plan. The type of heritage place also likely determines the duration of the management cycle and the level of operational detail of the management plan. It is important that planning processes consider both strategic and operational elements; whether these elements are included in the management plan itself or in other subsidiary plans is a decision to be made.

The Operational Guidelines determine that an integrated approach to planning and management is essential to guide the evolution of properties over time and to ensure maintenance of all aspects of their Outstanding Universal Value. As such, planning is essentially for:

- directing management towards a desired future rather than merely reacting to and proposing remedies to existing problems;

- ensuring that management responses are based on a clear understanding of the present situation of the heritage place and what has higher priority;

- forecasting potential future problems therefore providing guidance for managers to frame long-term strategic thinking as well as day-to-day operations;

- providing direction particularly in heritage places with complex governance arrangements, involving several managers;

- promoting continuity in contexts with high political or staff turnover; and

- promoting management effectiveness by defining desired outcomes and subsequently determining whether they have been achieved or not.

Planning is often considered a difficult, complicated and costly exercise, to be done because of statutory requirements and best left to specialised professionals. But not having a plan (or having one but not implementing it) is almost like trying to build a house without a blueprint. How do we decide on what the house is to look like, how much it will cost, how long it will take to build and who needs to be hired to build it? Planning offers a process that helps managers and actors decide how the heritage place should be managed, today and in the future.

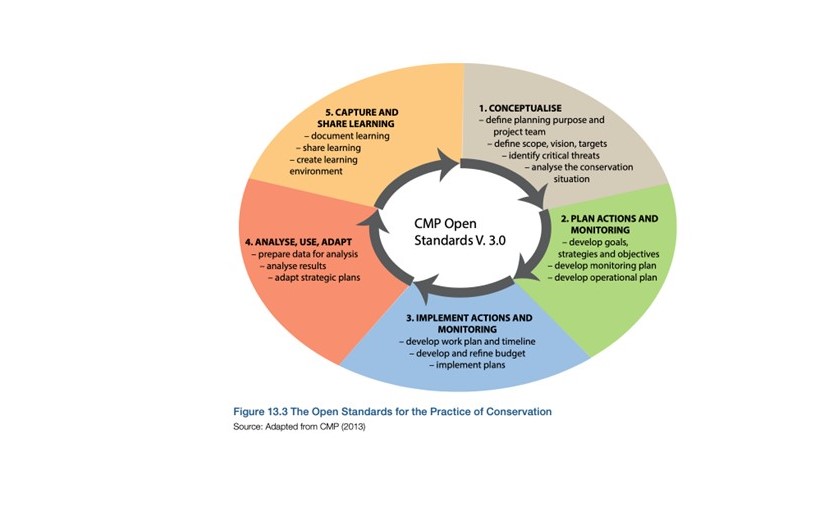

Planning is a continuous process. That is why planning is often presented as a series of clearly defined stages to be more easily understood, as in Figure…

Figure X.

In practice, planning is a complex whole, nested within and overlapping other processes and functions of the management system for the heritage place. To adequately envisage a desired future, we first need to know what the present situation is and what factors are affecting (or can potentially affect the heritage place). Those factors in turn can only be properly identified if there is a good understanding of the values and attributes of the heritage place and what the management objectives are. For example, if protecting certain attributes requires restricting access, then visitation may not be a priority for management, but research might. To know what factors are affecting the heritage place we also need to actively monitor the state of conservation. Therefore, planning cannot be simply explained as a recipe made of easy to follow step-by-step instructions in order to prepare a management plan. Instead, it needs to be conceived an iterative and dynamic process with different feedback loops, where different elements interact and inform each other, as suggested in Figure…

Outline of an iterative management planning process

How people get organised to develop that plan, what knowledge and information is used, who is involved, what procedures are followed, what criteria are used to formulate what is to be achieved (and the best course of action to get there) and who has the power to decide on all these aspects, matters enormously. All this is dependent on many things such as: the governance arrangements for the heritage place; how effective other elements of the management system are; what approach is taken towards preparing the management plan (e.g. if developed directly by managers or outsourced to consultants if in-house capacity is lacking); the resources available (e.g. if there is a need to look for extraordinary funding to develop the plan); or the purpose of the plan within the larger planning framework.

Planning is required at various geographic scales and organisational levels, which affect the management of the heritage place nevertheless. At national, provincial and municipal levels, planning activities determine which areas of land and sea will be used for what purpose and outline strategies for development. Management planning for heritage places can be seen as a subset process of this wider planning process and as a result, several ‘overlapping’ plans can coexist with the management plan for a heritage place, as in the case of large areas such as protected areas, cultural landscapes or urban settlements. Together these instruments constitute what is called the planning framework and can include a) broader planning instruments than those specific to the heritage place in terms of scale but also in terms of scope, and b) subsidiary plans, that detail particular management functions or areas of scope such as conservation plans, disaster risk management plans, sustainable tourism or visitor management plans or strategies, interpretation plans, business plans, etc..

When heritage places are subject to a variety of plans, it is crucial that the management plan for the heritage place is well integrated with broader land-use and development plans, given that what happens around the heritage place can deeply influence its state of conservation. If that is not the case, an otherwise well-developed management plan may not deliver the outcomes desired, if those broader plans pursue contrary objectives.

Management plans may be more or less strategic (versus operational), depending upon the purpose they have within the planning framework, the legal requirements they must meet and how well they are integrated with those other plans. A management plan with a timeframe of three to five years is likelier to be of a more operational nature, containing more detailed actions in response to existing challenges – since we are more certain about what may happen in the near future. A timeframe of ten or more years on the other hand encourages longer-term thinking, allowing to plan actions that may require considerable time until desired outcomes are achieved and as well anticipating future challenges and opportunities.

If we are to conserve heritage places for future generations, we need to think long-term. Since heritage places exist in an astonishing variety of categories, sizes and values they hold, in each place we need clarity on what exactly we need to do to protect it, particularly when the management system in place involves many and diverse managers and other actors. A first step towards this is to define clear management objectives.

Distinguishing between management objectives for the whole management system and what is to be achieved over a specific time period (and how to achieve it) often causes confusion. This is partly due to the fact that a confusing number of terms (e.g. ‘aim’, ‘goal’, ‘objective’, ‘vision’, ‘results’, ‘outcome’) is often used interchangeably. Because of their general and broad nature as guiding principles for the whole management system, management objectives are insufficient to guide planning. Since heritage places are affected by a range of factors, we need to regularly access the situation and then plan accordingly. Therefore, management objectives need to be completed by desired management outcomes, which define what is to be achieved over the duration of the management plan and other planning instruments, in response to those factors or potential future ones. For example, in a heritage place which constitutes an outstanding example of a traditional settlement constructed in wood, one of the management objectives may be: to maintain the traditional carpentry techniques. However, if the number of carpenters with the required skills is decreasing and is insufficient to meet the demand for reparation or maintenance works, something needs to be done about it. Therefore, a desired outcome to be included in the next management plan could be: number of carpenters trained in traditional buildings techniques increased by at least 20% by 2026.

Desired outcomes help translate the management objectives into work programmes during management planning processes. But some desired outcomes can take longer to achieve than others. For instance, the regeneration of coral reefs after bleaching events usually requires many years (when it is even possible). Similarly, introducing mitigation and adaptation measures to deal with the effects of climate change on a cultural landscape will also require longer and more strategic management responses. Such responses are better included in long-term strategies (sometimes also called strategic plans), offering a long-term perspective. These instruments should articulate the desired state, ideal condition or future of the heritage place, helping to guide its evolution over time while ensuring that its heritage values are maintained. Sometimes, this approach takes the form of a vision statement[1] often included directly in management plans, since generally few heritage places have long-term strategies or strategic plans. Whatever the terminology used, and how this is done, this long-term thinking is important; it should help setting strategic directions over what is to be achieved over a 20- or 30-years’ time horizon and what it is hoped the place will be like in the future. Shorter and medium terms desired outcomes can then be included in the management plan, that will put us on the defined path to achieve the long-term directions and desired state and can be important milestones or measures of progress.

Overemphasis on day-to-day management by responding to problems as they arise at the expense of long-term strategic directions and desired outcomes can lead to failure to put in place responses to factors affecting the heritage place, which require sustained management responses over time, and to deal with potential ones such as the effects of climate change.

[1] This vision is often articulated in conjunction with the mission statement of an organisation with management authority over the heritage place. This means that sometimes, that vision is directed mainly towards the function of the organisation rather than the heritage place itself.

In simple terms, a management plan is the main planning document to guide the management of a

World Heritage property

A cultural, natural or mixed heritage place inscribed on the World Heritage List and therefore considered to be of OUV for humanity. The responsibility for nominating a property to the World Heritage List falls upon the State(s) Party(ies) where it is located. The World Heritage Committee decides whether a property should be inscribed on the World Heritage List, taking into account the technical recommendations of the Advisory Bodies following rigorous evaluation processes.

When used as a general term, World Heritage refers to all the natural, cultural and mixed properties inscribed on the World Heritage List.

. The context of the management plan will depend on the characteristics of management system in place. In some cases, there will be a formal, legally binding, management plan, approved by a relevant authority but in others the plan may be less formal and exist mainly as an internal document. Sometimes the management plan can have a different name (e.g., conservation plan, safeguarding plan) but has the same purpose.

As the main product resulting from the planning process it is important to examine how the plan was developed. For instance, a plan mainly developed by an external consultant without much involvement from people who will be responsible for its implementation was based on a process that is different from that of a plan developed jointly by the people who are going to be responsible for its implementation and who will be affected by it. The actual implementation of the plan often depends on the planning process behind it: people may feel less committed to implement a plan which they did not help develop.

Legal requirements are often limited to public consultation of the draft final version of the management plan, before approval. However, participation should start as early as possible in the planning process and continue throughout all stages of the plan development. Two types of audiences must be considered: external actors (local communities and other rightsholders and stakeholders) and the staff who will be in charge of the plan’s implementation. For participation to be meaningful it is necessary that the draft of management is available to people in their own language. It is also crucial that people’s contributions are taken seriously and included in the plan, otherwise they will feel unheard and will not participate in future planning processes willingly.

As well as producing a more effective plan, participatory planning processes offer the following benefits:

- a better understanding of the heritage values and acceptance of the measures included in the plan;

- a mechanism for local communities and other rightsholders to participate in management and decision-making processes;

- opportunities to develop new ideas and thinking that can lead to innovation and approaching problems differently;

- institutional collaboration that can increase access to financial and other resources.

The scope and contents of a management plan vary considerably, depending on the type of property. For example, a management plan for an archaeological site or a single building may largely be a conservation plan, focusing on routine maintenance actions addressing the physical conditions of the place whereas that for an urban settlement may have a more policy-oriented nature, establishing priorities on how to address certain challenges, particularly if it is to be implemented by different managers. Similarly, a strict nature reserve may need a very different plan of that for an inhabited landscape with high biodiversity. There are detailed resource materials that offer detailed guidance on preparing management plans and that suggest approaches on how to structure it. When consulting those materials, it is important to keep in mind that the guidance they include should be adapted if needed to suit the particular context and characteristics of the heritage place you are working with.

Management planning for serial properties should consider both the needs of each component part as well as the property as a whole. The geographical and functional links between the component parts as well as the legal framework will dictate whether it is feasible to:

- have one overarching plan for the property as a whole; or alternatively,

- a strategic management planning framework for the whole property and different management plans (or similar instruments) for the individual component parts (or even for clusters of component parts). This approach can be particularly effective for transnational serial property requiring in intergovernmental agreements as the basis of coordination within the overall management system.

Whatever the approach taken, all management plans should nevertheless include certain elements and be based on sound planning principles, namely:

- Integrate the management of the property into the broader planning framework;

- Include a set of strategies and actions for achieving defined desired management outcomes and responding to the factors affecting the property;

- The content of the plan should be formulated within an adequate and current information base;

- Include clear guidance to assist managers in dealing with opportunities and eventualities that arise during the life of the plan, particularly if circumstances change considerably;

- Provide a programmed and prioritised set of activities and actions addressing both ongoing or routine maintenance actions and well as “one off” actions, which once completed do not need to be repeated (e.g. building a visitor centre) or which are part of a phased-out approach (e.g. enlarging the network of hiking trails);

- Provide a basis for monitoring the implementation of the plan and progress towards achieving defined desired management outcomes and adjustment of planning strategies and actions as required; and

- Identify the resources required to implement the programme of actions and ensure that they are realistically based on budgetary allocations of the managers responsible for the implementation.