Developing management plans

- The management plan is the product of the planning process which sets out what is to be achieved over a given period of time; it is an instrument to guide managers to implement actions in a planned and orderly way and to make the best use of the resources available in doing so.

- Developing a management plan can be broadly defined as the process used to establish how to get from the present situation to a desired state in the future.

- The preparation of a management plan for a heritage place should be formally initiated and launched by an institution with the mandate to manage the

World Heritage property

A cultural, natural or mixed heritage place inscribed on the World Heritage List and therefore considered to be of OUV for humanity. The responsibility for nominating a property to the World Heritage List falls upon the State(s) Party(ies) where it is located. The World Heritage Committee decides whether a property should be inscribed on the World Heritage List, taking into account the technical recommendations of the Advisory Bodies following rigorous evaluation processes.

When used as a general term, World Heritage refers to all the natural, cultural and mixed properties inscribed on the World Heritage List. , and a person or team should be identified and assigned responsibility for drafting the management plan. - Collaboration between all managers and the participation of rights-holders and relevant stakeholders should start as early as possible in the planning process and continue throughout all stages of development.

- The starting point for any management plan must be a thorough understanding of the heritage place, as well as of the management system in place.

- Management objectives are very important as guiding principles for the whole management system over a long timeframe, therefore it is useful to complement them with desired outcomes, determining exactly what is to be achieved within the duration of the management plan being developed.

- A management plan should include a practical programme of actions that will ensure the desired outcomes will be achieved. It should detail what actions are to be implemented, who will be responsible for their implementation, when they are to be implemented, what human capacity and financial resources are needed and who will provide those resources.

- The management plan constitutes a commitment from managers on how the heritage place is to be managed today and in the coming years and should therefore be readily available and transparent to ensure all actors are aware of the plan’s desired outcomes.

- Many heritage places use subsidiary plans that need to be carefully integrated and harmonized within the management plan and their implementation needs to be equally ensured.

Developing a management plan can be broadly defined as the process used to establish how to get from the present situation to a desired state in the future. Managers will need to ensure that management planning supports management objectives, and that they are realistic in relation to the resources available.

The management plan is the product of the planning process, which sets out what is to be achieved over a given period of time – it is an instrument to guide managers to implement actions in a planned and orderly way and to make the best use of the resources available in doing so.

The quality of the process is as important as the content of the plan itself because, if done in a participatory manner as is recommended, it offers opportunities for all actors to come together, coordinate and exchange diverse understandings and perspectives over the future of the heritage place and what should be done to protect it.

The status of the management plan will depend on the characteristics of the management system in place. In most cases, there will be a formal, legally binding, management plan, approved by a relevant authority; in others the plan may be less formal and exist as a guiding document or an agreement between relevant actors. It remains important that the management plan is readily available and transparent to ensure all actors are aware of the plan’s aspirations.

The scope and contents of a management plan vary considerably, depending on the type of property. For example, a management plan for an archaeological site or a single building may focus largely on conservation and routine maintenance actions addressing the physical conditions of the place; whereas that for an urban settlement may have a more policy-oriented nature, establishing priorities on how to address certain challenges, particularly if it is to be implemented by different managers. Similarly, a nature reserve may need a very different plan from that for an inhabited protected landscape or a large marine ecosystem which includes a sustainable fishing zoning.

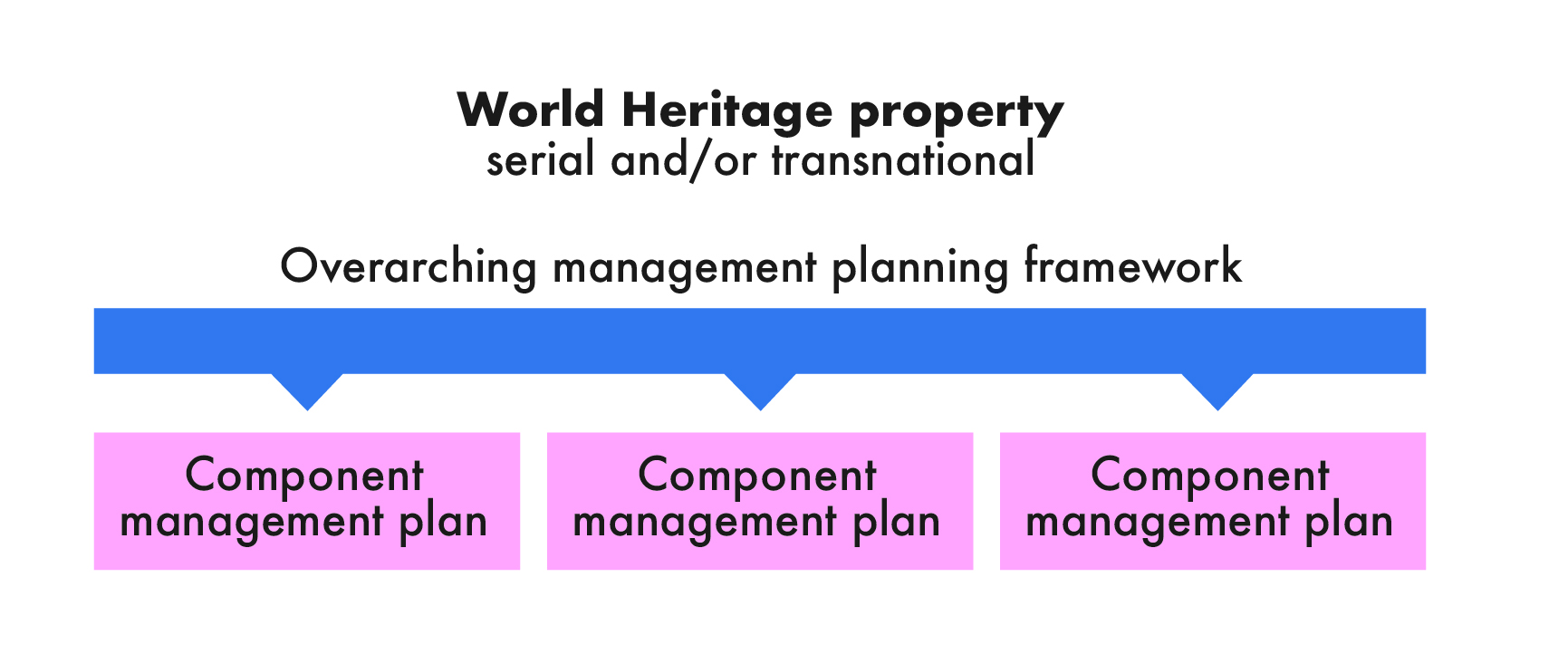

Management planning for serial properties should consider both the needs of each component part, as well as the property as a whole. The geographical and functional links between the component parts, as well as the legal framework, will dictate whether it is feasible to have one overarching management plan for the property as a whole; or alternatively, have an overarching management planning framework for the whole property and different management plans for the individual component parts (or even for clusters of component parts). This approach can be particularly effective for a transnational serial property requiring intergovernmental agreements as the basis of coordination within the overall management system. In many cases, only plans at individual place level are likely to be legally binding so the overarching management planning framework may fulfil more of a coordination function across multiple plans.

Figure 5.2. A transnational serial property would require intergovernmental agreements as the basis of coordination with an overarching management planning framework for the whole property and different management plans for the individual component parts (or even for clusters of component parts).

Planning processes should strive to:

- ensure that a participatory and human rights-based approach is taken to the planning process, with the effective involvement of all managers, rights-holders and relevant stakeholders that includes appropriate considerations for setting the mechanisms and allocating the resources and time needed for such an approach;

- integrate the management of the property into the broader planning framework;

- formulate the content of the plan with an adequate and up-to-date information base.

Based on these approaches, all management plans should include:

- a comprehensive mapping of heritage values and attributes conveying those values;

- a baseline of the conservation state of the heritage attributes that takes into account the state of conservation at the time of inscription and the current state;

- a detailed understanding of the factors affecting the property and the management measures needed to respond to it;

- alignment with clearly agreed management objectives for the management system as a whole which includes a set of desired management outcomes to be achieved over the duration of the plan, supported by a programme of actions detailing how to do it;

- the addressing of both ongoing or routine maintenance actions and well as one off actions or single management interventions (examples might be building a visitor centre as well as enlarging the network of hiking trails or digitally recording built heritage interiors);

- identification of the resources required to implement the programme of actions and ensure that they are realistic;

- the setting of clear timeframes and accountabilities for the implementation of the programme of actions;

- clear guidance to assist managers in dealing with opportunities and eventualities that arise during the implementation of the plan, particularly if circumstances change considerably;

- assigning of clear accountabilities for the programme of actions;

- a basis for monitoring the implementation of the plan and progress towards achieving defined desired management outcomes and the adjustment of planned actions as required;

- mechanisms for the periodic review and evaluation of the implementation and achieved outcomes to identify points of improvement for the future.

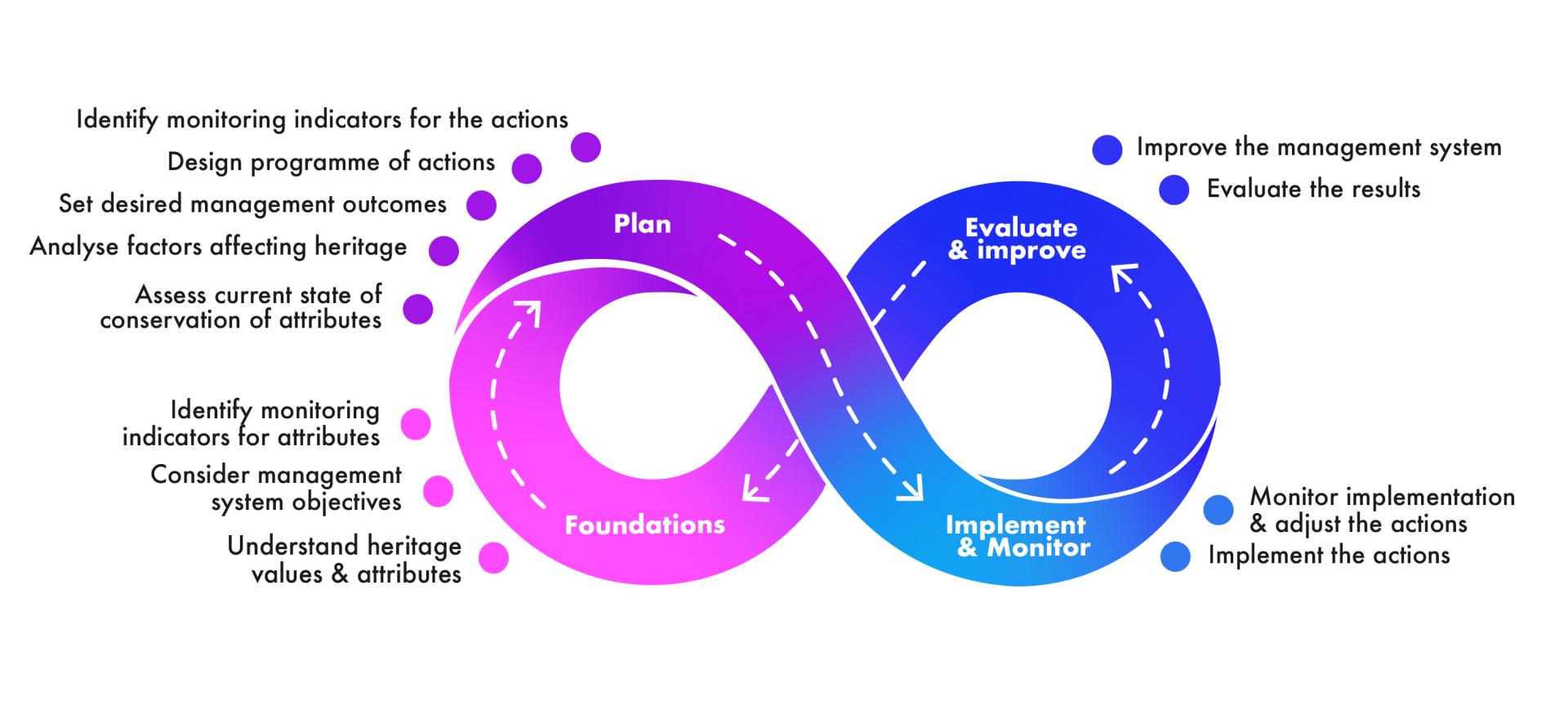

Figure 5.3 Diagram that outlines an iterative management planning process

The diagram above shows that while the preparation of a heritage management plan is a critical step, it is only the beginning since the work continues with its implementation and monitoring and evaluation. These different processes combined – planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation – constitute a management cycle, which is then repeated with the next management plan.

The following sections provide a general overview of the steps that can be followed when preparing a management plan. While the text refers to the preparation of the main management plan for a heritage place, the general approach can be used for preparing any plan, from broad long-term strategic plans (covering perhaps 20-30 years) through to subsidiary plans (i.e. risk management plan, visitor management plan or heritage interpretation plan).

The preparation of a management plan for a heritage place should be authorized by a relevant institution and have the support of the key decision-makers who will have to approve its adoption and enable its implementation, monitoring and evaluation. In some countries, the development of a management plan is required by law, particularly for World Heritage All inherited assets which people value for reasons beyond mere utility. Heritage is a broad concept and includes shared legacies from the natural environment, the creations of humans and the creations and interactions between humans and nature. It encompasses built, terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments, landscapes and seascapes, biodiversity, geodiversity, collections, cultural practices, knowledge, living experiences, etc. properties, and can be triggered at the national level. However, the process of initiating and drafting the plan should be done at the property or local level and led by the managers with primary responsibility for conserving and managing the heritage place.

Typically, a person or team will be identified and assigned the responsibility of drafting the management plan to control the process of timing and budget. While priority should be placed on having in-house managers, external consultants may also be involved in this role. The designated person or team should be chosen for their abilities to coordinate with all other actors and facilitate the drafting process while taking into account the in-depth knowledge about the existing management system and the heritage place.

For an effective planning process engaging all actors, but particularly for properties that are governed by multiple managers extending beyond one administrative area or country, a steering group or committee consisting of key representatives of the institutions involved should be established to oversee the planning process. When a steering committee is established, clear reporting and decision-making mechanisms between the team responsible for developing the plan and the committee must also be established.

Governance arrangements determine who is responsible for leading the planning process and who must be involved. Collaboration between all managers and the participation of rights-holders and relevant stakeholders should start as early as possible in the planning process and continue throughout all stages of development.

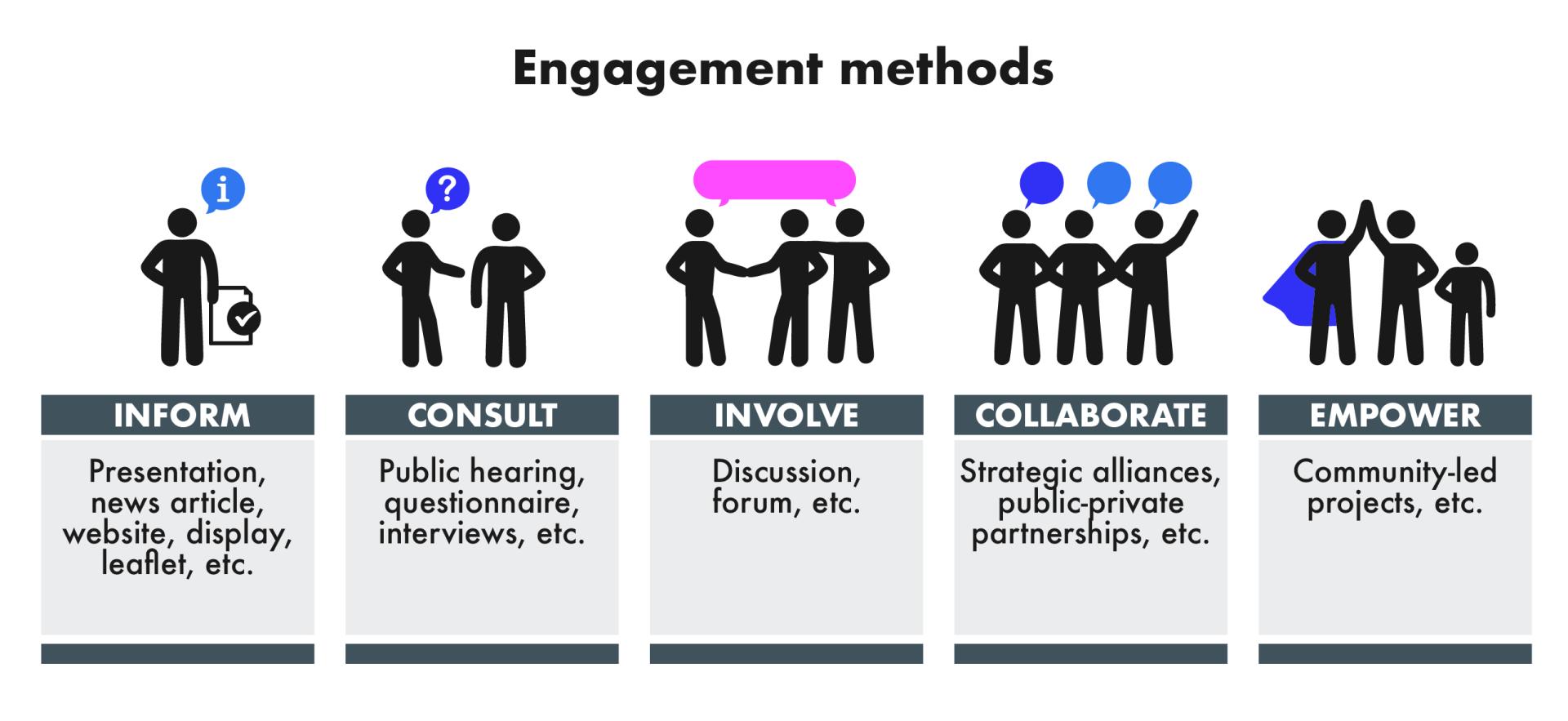

Figure 5.4 Engagement methods for rights-holders, local communities and other stakeholders. Engagement can take various forms throughout a planning process. Different approaches will be needed for different individuals and groups, but techniques that provide people with an active role are generally preferable to the passive provision of information. Source: Guidance and Toolkit on

Impact

The effects or consequences of a factor on the attributes of the heritage place, both in terms of the attributes’ state of conservation and their ability to convey the heritage/ conservation values. An impact is the difference between a future environmental condition with the implementation of a development project, and the future condition without it. Note that for there to be an impact, there must a source of impact (e.g. noise from an industrial site), a receptor or attribute of the

World Heritage property

A cultural, natural or mixed heritage place inscribed on the World Heritage List and therefore considered to be of OUV for humanity. The responsibility for nominating a property to the World Heritage List falls upon the State(s) Party(ies) where it is located. The World Heritage Committee decides whether a property should be inscribed on the World Heritage List, taking into account the technical recommendations of the Advisory Bodies following rigorous evaluation processes.

When used as a general term, World Heritage refers to all the natural, cultural and mixed properties inscribed on the World Heritage List.

that is affected (e.g. residents living nearby) and a pathway or route by which the harmful action or material is able to reach the receptor (e.g. the air). Impacts can be positive or negative, as well as direct or indirect, current or potential and originating within the heritage place, any existing buffer zone(s) and even beyond it.

See also: Direct impact,

Indirect impacts

Indirect impacts are impacts on the environment which are not a direct result of the project, often produced away from or as a result of a complex pathway. Sometimes referred to as ‘second’ or ‘third-level’ impacts, or ‘secondary’ impacts.

See also: Impact, Direct impacts, Cumulative impacts

, Cumulative impacts

Assessments in a World

Heritage

All inherited assets which people value for reasons beyond mere utility. Heritage is a broad concept and includes shared legacies from the natural environment, the creations of humans and the creations and interactions between humans and nature. It encompasses built, terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments, landscapes and seascapes, biodiversity, geodiversity, collections, cultural practices, knowledge, living experiences, etc.

Context.

Independent of who takes the lead in developing the management plan, all managers will need to be involved in the entire planning process. The plan will be much more effective if developed jointly by the people who are going to be responsible for its implementation. Implementation often depends on the planning process behind: people may feel less committed to implement a plan they did not help develop.

Legal requirements for public participation are often limited to consultation on the final draft of the management plan before it is approved. However, genuine participation takes different forms at different stages, involving actors in a variety of ways according to their rights, roles and responsibilities. For example, issue briefs might be developed and shared to consult on key matters or community focus groups convened to gauge and effectively incorporate their views. Too often, rights-holders are only heard but their views and proposals are not effectively included in the resulting management plans. When consulting rights-holders, remember that they also have the right to know how their input is being included in the plan. Where Indigenous Peoples are affected, the planning process must be adapted to ensure their full and effective participation, through their own freely chosen representatives and institutions and in a climate of mutual trust and transparency.

For participation to be meaningful it is necessary that communication and the draft plans are available to people in their own language and in a timely manner, with any meetings organized in a way sympathetic to people’s needs. It is also crucial that people’s contributions are taken seriously so that strong relationships are built among all actors, facilitating management over time.

As well as producing a more effective plan, participatory planning processes offer the following benefits:

- a better understanding of the heritage values and acceptance of the measures included in the plan;

- a mechanism for rights-holders and local communities to participate effectively in management and decision-making processes;

- opportunities to develop new ideas and thinking that can lead to innovation and a new approach to challenges;

- collaboration that can increase access to financial and other resources, and their effective, just and equitable use.

The starting point for any management plan must be a thorough understanding of the heritage place, as discussed in Part 3, as well as of the management system in place. This will involve:

- Understanding the OUV and other important heritage values of the

World Heritage property

A cultural, natural or mixed heritage place inscribed on the World Heritage List and therefore considered to be of OUV for humanity. The responsibility for nominating a property to the World Heritage List falls upon the State(s) Party(ies) where it is located. The World Heritage Committee decides whether a property should be inscribed on the World Heritage List, taking into account the technical recommendations of the Advisory Bodies following rigorous evaluation processes.

When used as a general term, World Heritage refers to all the natural, cultural and mixed properties inscribed on the World Heritage List. , and the attributes that convey it; - Understanding the broader social, cultural, economic and environmental context;

- Understanding the governance arrangements (including all the actors involved), applicable legislations and regulations, and the broader planning framework within which the management plan will be integrated;

- Determining the current state of conservation of the property; and

- Analysing in detail the factors affecting the property, how they affect the property positively or negatively and what are the impacts on the attributes.

Gaining a detailed understanding of all these aspects is a lengthy and ongoing task and not all of the information gathered will need to be included in the main text of the management plan. However, it is essential to inform the overall management planning process and ensure that the programme of actions included in the plan is effective. Since heritage places are affected by a range of factors, regular monitoring of the situation is needed with adjustments where necessary and within defined criteria and precise moments of the management cycle.

It is essential to have a clear understanding of what needs to be done to protect a heritage place, something which is influenced by its typology, size and range of heritage values. The sharing of this understanding becomes particularly important when multiple managers are involved. For this reason, the definition of objectives guiding the actions of the management system is very important (see 2.3). These objectives may be relatively generic as they serve as guiding principles for the whole management system. That is why they need to be complemented with desired outcomes, determining what is to be achieved within the duration of the plan being developed.

Setting desired outcomes is dependent on the duration of the management plan. A management plan with a timeframe of 3-5 years is likelier to be of a more operational nature, containing more detailed actions in response to existing challenges – since managers are more certain about what may happen in the near future. For management plans with a longer duration (5-10 years), short- and medium-term desired outcomes can be important milestones or measures of progress to evaluate whether the implementation of concrete actions is delivering what was expected and the overall effectiveness of the management plan. For long-term plans monitoring the shorter term outputs regularly offer timely opportunities to reassess if circumstances have changed over time and if adjustments are needed.

For example, in a heritage place which constitutes an outstanding example of a traditional settlement constructed in wood, one of the management objectives of the management system might be to maintain the traditional carpentry techniques used. However, if the number of carpenters with the required skills is decreasing and is insufficient to meet the demand for reparation or maintenance works, something needs to be done. Therefore, a desired outcome to be included in the next management plan could be to increase the number of carpenters trained in traditional building techniques by at least 20% in 5 years.

Ensuring that desired outcomes are aligned with management objectives is fundamental. The objectives provide the possibility to adopt long-term thinking in anticipating future challenges and opportunities, rather than responding to problems as they arise.

Once desired management outcomes have been clearly defined, actions need to be identified that will ensure that those outcomes are achieved. Any type of plan can be accompanied by a practical programme of actions which details which are to be implemented, who will be responsible for their implementation, when they are to be implemented, what human capacity and financial resources are needed and who will provide those resources. The programme of actions should be included as a section of a management plan. For short- and medium-term management plans (i.e. 3-5 years), the programme of actions can be detailed enough to guide implementation. However, in the case of plans covering long timeframes (i.e. 5-10 years or more), it is difficult to plan in detail so far ahead and the programme of actions will likely include strategic provisions of what is to be implemented, rather than detailed actions. In such cases, the programme of actions will need to be complemented by more detailed annual or biannual work plans, linked to annual or multi-year budgeting processes.

The work plans help translate the strategic provisions of the management plan into an operational programme of actions. A sequence of work plans can be developed one at a time which respond to the current situation and the immediate period ahead. For example, a ten-year plan might be accompanied by five biennial work plans that are developed and implemented one after another. Many institutions develop short-term work plans (i.e. generally 1-2 years) once there is certainty about the resources available and budgets have been approved. Their development offers an opportunity to reassess if circumstances have changed compared to the provisions included in the management plan and if adjustments are needed. The work plan can then detail a programme of actions that is feasible to implement, which will produce the outputs of the management plan, that measures the productivity of the management system.

Many heritage places use other important subsidiary plans (e.g. DRM plan, fire, invasive species, visitor management, interpretation) that need to be carefully integrated and harmonized with the management plan and their implementation ensured. In these situations, work plans can play a critical role as an instrument to combine the implementation of the programme of actions included in the different plans and ensure that the number of actions to be implemented per year is evenly distributed, without creating an unrealistic workload or over-allocating budget.

For heritage places managed mainly by a single institution, the logic and flow of developing and implementing the management plan, as well as any subsidiary plans and subsequent work plans should be relatively straightforward. However, many heritage places have complex governance arrangements, where the implementation of any plan requires the collective effort of different managers. It can also happen that managers hold responsibilities that extend beyond the

World Heritage property

A cultural, natural or mixed heritage place inscribed on the World Heritage List and therefore considered to be of OUV for humanity. The responsibility for nominating a property to the World Heritage List falls upon the State(s) Party(ies) where it is located. The World Heritage Committee decides whether a property should be inscribed on the World Heritage List, taking into account the technical recommendations of the Advisory Bodies following rigorous evaluation processes.

When used as a general term, World Heritage refers to all the natural, cultural and mixed properties inscribed on the World Heritage List.

, such as, for example, a nature conservation agency responsible for the management of a regional network of protected areas or a municipality which manages several conservation areas within a wider historic urban landscape. This can make implementation of any plan more complex. In such cases, the more detailed the programme of actions and subsidiary works plans are, the easier implementation will be.

The finalized management plan should be adopted and authorized by the relevant institution and key decision-makers. For World Heritage All inherited assets which people value for reasons beyond mere utility. Heritage is a broad concept and includes shared legacies from the natural environment, the creations of humans and the creations and interactions between humans and nature. It encompasses built, terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments, landscapes and seascapes, biodiversity, geodiversity, collections, cultural practices, knowledge, living experiences, etc. , some countries require management plans to be approved at the national level. Having a formal process to adopt and authorize the management plan will ensure the support of the key decision-makers, and enable its implementation, monitoring and evaluation. It will also facilitate the allocation of necessary resources needed to implement the plan.

- Have all managers contributed to and been appropriately involved in the development of the management plan?

- Have all rights-holders and key stakeholders been identified and appropriately engaged in the development of the management plan?

- Are the management objectives clearly linked to the values and attributes of the property?

- Are the management objectives specific enough to guide the management system for the property?

- Does the management plan have a defined timeframe for its implementation? Why is this timeframe established?

- Are the desired outcomes and the programme of actions within the heritage place’s management plan adequately detailed to guide implementation? If needed, are work plans developed to complement the programme of actions?

- Are clear priorities agreed upon, in line with the objectives for the heritage place, so that the plan includes a realistic programme of actions that matches the human resources and funds likely to be available?

- Are subsidiary plans (e.g. on tourism, DRM or threatened species recovery, etc.) consistent with the heritage place’s provisions in the main management plan?

- Is the programme of actions in the management plan realistic in terms of available resources (budget, technical capacity, timeframes)?

- Is the management plan formally adopted/authorized by the relevant institution?

- If discrepancies exist between the provisions included in the management plan and those in other plans, is it clear that the provisions in the management plan should prevail?

- IUCN Protected Areas Programme (2008), Management Planning for Natural World Heritage All inherited assets which people value for reasons beyond mere utility. Heritage is a broad concept and includes shared legacies from the natural environment, the creations of humans and the creations and interactions between humans and nature. It encompasses built, terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments, landscapes and seascapes, biodiversity, geodiversity, collections, cultural practices, knowledge, living experiences, etc. Properties, pp 35. Gland (Switzerland), IUCN.

- Appendix A ‘A framework for developing, implementing and monitoring a management plan’ in the manual Managing Cultural World Heritage All inherited assets which people value for reasons beyond mere utility. Heritage is a broad concept and includes shared legacies from the natural environment, the creations of humans and the creations and interactions between humans and nature. It encompasses built, terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments, landscapes and seascapes, biodiversity, geodiversity, collections, cultural practices, knowledge, living experiences, etc. . Paris, UNESCO.